3-2-1: 501 Main Comes Down, The Case For Tax Abatements, Should Town Sewer Be Prioritized?, & More

Issue #25

Happy Sunday —

Here are 3 things from others, 2 things from me, and 1 picture related to incremental real estate development and my projects at Village Ventures.

Enjoy!

THREE THINGS FROM OTHERS

I. The Case For Property Tax Abatements

Des Moines, IA has a robust tax incentive program for new development. This includes 10-year abatements for rehab, commercial, and industrial projects.

Last year, the city expanded its incentive program to encourage Missing Middle housing and accessory dwelling units (ADUs).

Specifically, Des Moines offers:

An 8-year declining tax abatement for buildings with 2-12 housing units

An extra year of tax abatement added for buildings that hit sustainability targets—namely, R-20 insulated walls and level 2 EV charger infrastructure

A 10-year 100% tax abatement for detached ADUs

How Des Moines’ tax abatement program works

So do these property owners just pay $0 in property taxes during the abatement period?

No.

This is a common misconception about tax abatements.

Rather, the property owner avoids any additional property taxes incurred from the increase in assessed value associated with the project.

Here’s an example.

Say I own a tired, vacant property with an assessed value of $200,000 and pay $5,000 in property taxes annually (2.5%).

In an effort to create new housing opportunities and drive downtown revitalization, I invest $1M to redevelop the building into a 3-story residential and retail space.

After completion, the new assessed value is $500,000 (remember, assessed value does not equal market value). My new unabated yearly tax bill is then $500,000 * 2.5% = $12,500.

Under Des Moines’ Missing Middle tax incentive program, I would continue to pay the baseline $5,000 for a few years, gradually stepping up to the full $12,500 after eight years.

Des Moines’ actual abatement schedule for its Missing Middle program is: 100-100-100-100-100-75-50-25%.

That is—in Year 1, 100% of the new assessed value ($500,000 - $200,000 = $300,000) is exempt from taxation. In Year 6, 75% is exempt and I pay $1,875 (2.5% * 25% of $300,000) in addition to the baseline $5,000. After that, the incentive decreases until Year 9, at which point I pay the full $12,500 annually.

Importantly, the city does not take a reduction in tax revenue. Rather, it temporarily forgoes additional revenue above and beyond what it collects today.

The power of tax abatements

Tax abatement provides a powerful mechanism to stimulate targeted growth and investment.

Often, municipalities will employ the “but-for” test to determine qualification—a project only qualifies if the sponsor can prove that it will not move forward without the tax abatement.

The overarching benefit of a tax abatement program is the expedited revitalization of downtown areas. Projects that typically would go undeveloped due to financial constraints may now pencil out. And, after the abatement expires, a project should be able to absorb the added tax burden as a result of natural rent increases and debt principal pay-down over the years.

Tangentially, there are larger economic development implications as well. A recent study shows that for every $1 of property tax abated, $40 is added to the local economy.

Oh, and the example I gave above? Those are the actual figures for my 501 Main project in Fairlee, VT (with rounded numbers). Including the estimated assessed value post-completion from the town lister.

Unfortunately, Fairlee does not (yet?) have a tax abatement program. But some sort of program seems like it would align well with the town’s goals of spurring smart growth in the village center.

Here are a couple resources to dive further:

Des Moines’ bylaws showing how they structured their abatement program

The National Housing Conference’s policy guide to tax abatements

II. What Is Missing Middle Housing?

I’m a big proponent of Missing Middle housing (MMH)—neighborhood-scale development of buildings with 2-20 units.

MMH is enticing for a few reasons:

Its scale is appropriate to achieve the density needed for walkable, vibrant downtowns (10-20 dwelling units per acre)

It can be built and maintained by small developers, bringing quality new housing to the market without large apartment players getting involved

It has the ability to create and retain wealth in the community through individual ownership (e.g. owner-occupied triplex or small-time landlords)

Building MMH affordably is a hurdle. Almost by definition, it is not standardized and can be difficult to achieve economies of scale. Although some, like Homes Homes, have had success delivering Missing Middle townhomes for $200,000.

For those unfamiliar with MMH, its creator (or rather, the architect that coined the term)—Daniel Parolek—just released a short video that’s worth a watch:

III. The Debate Over Municipal Sewer Systems

I read the article by Strong Towns recently titled Sorry, but a $10 Million Sewer System Won't Fix Your Economy.

I usually agree with the perspectives that Strong Towns produces. But this one hasn’t sat well with me.

The story centers on Island Falls, Maine (population 781) that, as you might have guessed, sought federal support for sewer infrastructure in their village center. All in an effort to drive economic development and downtown revitalization.

The author thinks this is foolhardy. And that there are 1,000 other ideas for small, affordable steps a community might take if they want to help encourage small business activity and build up their downtown.

I get the argument. Sewer systems are egregiously expensive—both the installation and ongoing maintenance. Federal dollars will only help with installation. Towns and residents may not be prepared for the inevitable cost of future maintenance.

And yes, there are alternative, low-cost strategies a town can take to promote economic development.

At the end of the day, though, a sewer system is an integral building block to drive smart growth and minimize sprawl. If every property owner has to put a septic system on their property, the community will not experience the dense development necessary to support a walkable, vibrant area.

The town where I’m developing 501 Main—Fairlee, VT—does not have a municipal sewer system either.

For reference, take a look at the septic system I’m required to install for eight apartments and one retail space.

I’m lucky that my 0.5 acre lot can accommodate the septic (and parking). But many sites don’t have the “luxury” of hidden land behind Main Street.

Fairlee hasn’t seen new development in decades. And this is despite having a community and town policies encouraging it. Sure, there may be other factors suppressing growth, but it would be unfair to say that the lack of a sewer system hasn’t played a role.

My feeling is that municipal sewer is actually more foundational than nice-to-have. It inherently reduces minimum lot sizes—at 501 Main, the onsite septic system accounts for ⅓ to ½ of the developed land. And, most importantly, it allows for denser development.

Look at any thriving, dense, walkable downtown and you’ll see they have municipal sewer. It’s no coincidence.

That said, the financials certainly need to be evaluated. And the town needs to be aligned on wanting to promote dense growth in the village center.

It all comes down to the math. But there’s a recognizable difference in paying $10M upfront for installation vs paying ongoing maintenance fees for usage. Most towns don’t have the funds lying around for such a large capital expense. Yet they likely have the capacity to pay for maintenance in perpetuity via future impact and usage fees.

I don’t actually see an issue with using federal dollars for the installation as long as the town sets out a clear path to maintain the system in a self-sufficient manner.

What is your perspective on prioritizing municipal sewer? Or your response to the Strong Towns’ article?

I’m genuinely curious. Please leave a comment below. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

TWO THINGS FROM ME

I. 501 Main is gone!

We demolished 501 Main this week and, man, it feels good to see some real progress!

Five hours from start to finish with an excavator. Five hours. That’s it. And four 30-yard dumpsters.

What’s crazy is that I even attempted to deconstruct the building by hand. All-in, I’d estimate that would've taken 120+ hours. With another 20 to de-nail the wood.

Before I came to my senses, I had 15 hours into removing all the reusable items (windows, doors, boiler, etc) and scrap metal. And another 20 into demo.

Solid lesson learned. But I’m still happy we were able to find new homes for most of the reusable items—a homeowner couple took the insulation for their new house and I donated the pile of 1x4 trim board to the local trade school.

The excavator made me nervous knowing we had to keep the foundation and floor system intact. I even went around the building the day before with a skill saw and Sawzall to rip the sheathing at the rim joist.

But, in the end, my site contractor (shoutout to Nate Locke) was flawless in execution. It’s amazing how precise such a massive machine can be with an expert operator at the helm.

The last piece of demo we have remaining is the removal of the subfloor—substantial reinforcement is needed to the joist system to prepare to build up and this will allow easy access to it. We will have to do this by hand.

In parallel, we’ll pour 30’ of new footing and frost wall in order to square off the building (you’ll see in the picture above that the foundation is slightly L-shaped today).

II. Powering 501 Main

Bringing sufficient electrical power to 501 Main has either been a compelling thought exercise or severe headache depending on the day.

It’s certainly not something I anticipated having to spend so much time on.

If you’re looking at redeveloping a building into a higher use, it’s worth having some sort of strategy defined up front. Because it’s not always as easy as just tapping into the closest power line.

In January, I discussed a few options we were looking at for getting power to the site.

That thinking has continued to evolve. Both as a result of my electrician getting more involved and me learning more about the nuances of supplying power to a building.

For any new development, an electrician will conduct a load calculation—essentially, they’ll add up all the various electrical demands for the project (outlets, appliances, heating system, etc). This number will determine the size of the power service requested from the utility company.

The building previously had a 200 amp service. We will need 670 amps for the new one.

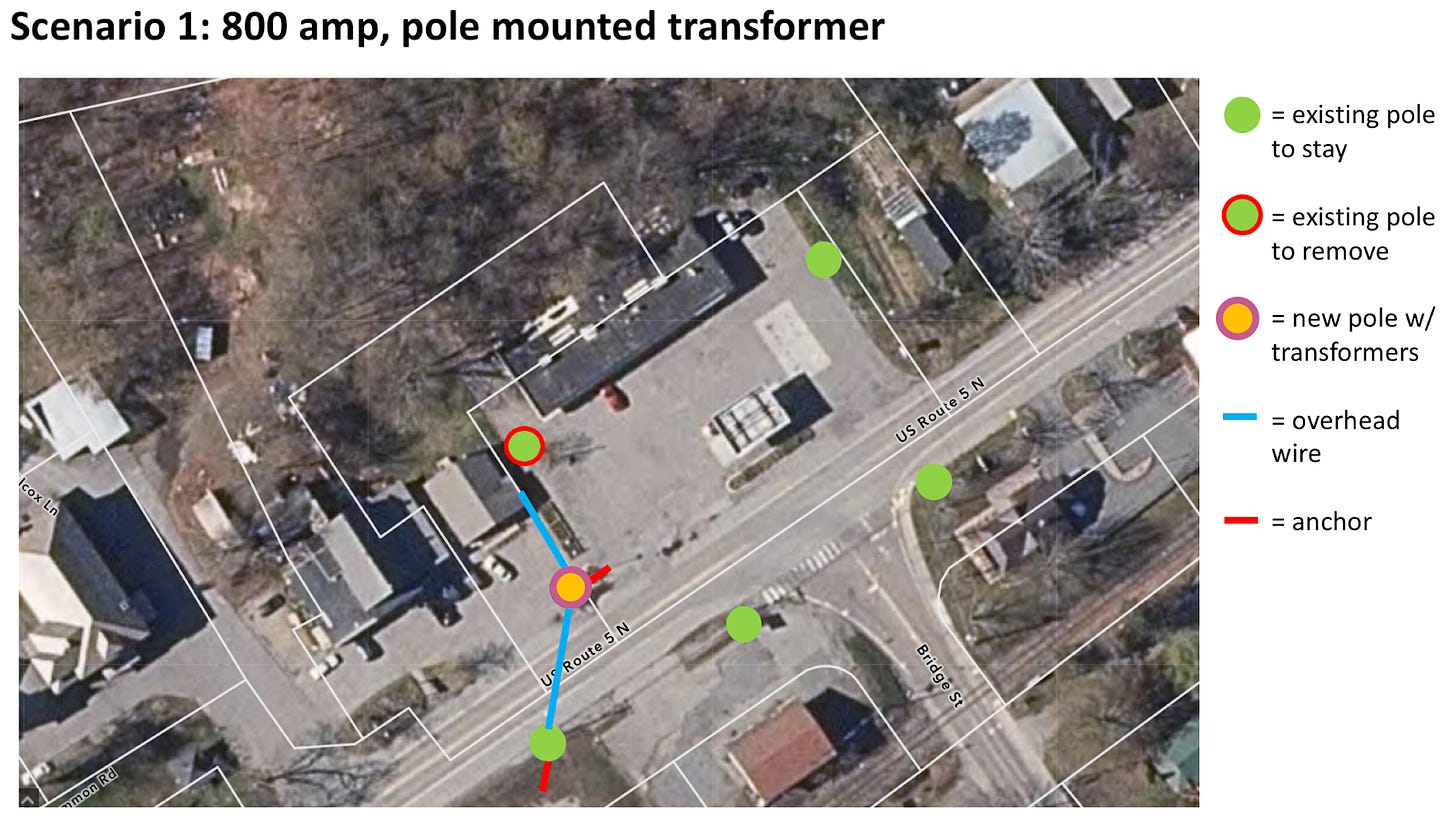

There are a few variables to juggle when mapping out how we’ll run service to 501 Main:

The pole providing service to the building previously sits in the center of the driveway needed to access the new parking lot out back. It will have to be removed

The next closest pole is across the street. An overhead service drop (the wire going from pole to building) can only span 100’ according to VT utility code. Unfortunately, that pole is 110’ away so some intermediary pole will be needed

Utility companies provide power service in increments—for this project, we can either go with 800 amps or 1200 amps. 1200 amps allows for more flexibility with future EV charging but requires ~$20k in additional upfront cost (3-phase power + pad mounted transformer vs single-phase + pole mounted)

Pole anchors (i.e. the metal wires that come off the top of the pole at 45° angles to secure the pole in the ground) need to be accounted for. For example, Scenario 1 below would require anchors extending 15’ from the base of the poles on 501 Main and the property across the street. Permission would need to be obtained from affected property owners before the utility company could proceed

Here are two scenarios I’m looking at. 501 Main is the L-shaped lot in the center.

Scenario 1 costs $4,500 in utility company fees (the customer is responsible for new poles, additional wire installation, and transformer upgrades). Scenario 2 is $7,500. This is outside any excavation or electrician costs to run conduit and cable for the service entry into the building.

The major benefit of Scenario 2 is the ability to eliminate street-side wires and poles that detract from the building’s curb appeal (and view from balconies). This would also eliminate anchors out front which would affect flow and layout of my parking lot.

Still TBD though. A few more conversations to be had before finalizing.

ONE PICTURE

Here’s your ADU inspiration for the week. Imagine one of these in your backyard!

📍Portland, OR

Source: Neil Kelly Company

That’s it for today. Thanks for reading. If you haven’t yet, go ahead and subscribe here:

About me: I’m Jonah Richard, a small-scale real estate developer in Vermont. With my company, Village Ventures, I’m currently getting my hands dirty developing Missing Middle housing while trying to pick apart and replicate what makes other communities thrive.

Connect with me on LinkedIn and follow my projects on TikTok.

I just finished reading Arthur Kahn's sad note of the failure of the nascent Thetford Arthouse Cinema (www.thetfordcinema.org) to find a space in Thetford's community building, as his proposal was rejected by a few members of the Thetford Community Center Association. He mentioned maybe Norwich could be a possible alternative in the future, so I immediately thought "why look south?" and wondered if such a venue could be possible in Fairlee?

Niles

1. Love the drone pics.

2. Appreciate the thoughtful response to the ST article. Challenging ideas is good for us all.

3. The 800A single phase pole mounted transformer feels right. Hopefully you can find a way to make the extra cost of scenario 2 work out!