Morning!

Latest 3-2-1 here from Brick + Mortar about real estate development and creating great places.

3 things from others

2 things from me

1 picture

Care to share?

3 THINGS FROM OTHERS

I.

Row houses are like the Airstreams of real estate—constantly being converted and adapted to new uses. Single-family living, ground-floor retail, top-floor office. You name it.

They’re also iconic. Most major urban centers still retain some form of row houses unique to that location. And, today, many are being subdivided into apartment units to meet market demand.

Perhaps most inspiring though, are their applicability to affordable housing (top left image below). Due to their compact size, some developers have begun to re-establish the row house as a place for the people, rather than just the elite.

Source: The Rise and Resurgence of the Great American Row House

II.

I’ll give parking minimums a rest after this week but this was too good not to share.

In a landslide vote, St. Pauls, MI just became the latest city to eliminate parking minimums. Entirely. That means no more having to sift through dense zoning code to calculate arbitrary numbers of parking spots required.

This latest victory follows a burgeoning trend in zoning philosophy starting with Buffalo, NY in 2017, then followed by San Francisco in 2018, and Minneapolis, Sacramento and Berkeley in 2021.

One factor that helped push this through was the discovery that 36% of the city’s land mass was dedicated to moving or storing cars. Thirty-six percent!

For a city with a goal of reducing vehicle miles traveled by 40 percent by the year 2040 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, they have a ways to go. This is, though, one step in the right direction.

Source: St. Paul Eliminates Parking Minimums

III.

Want to add another story to your house? Here’s an alternative to removing the roof and building up.

Just, please, promise to practice better façade design…

2 THINGS FROM ME

I.

Housing affordability is often misunderstood.

The trite suggestion of “We need more affordable housing” seems guaranteed to get a bunch of head nods in any community meeting.

And rightly so. Homes and apartments are notoriously unattainable for the general population.

As an example, take Vermont where the average home costs $300,000. With a 20% down payment, that’s a monthly bill of around $1,650 including mortgage, taxes, insurance, and utilities.

The general rule of thumb is that households should only spend 30% of their income on housing. Only problem is—the average 3-person household in Vermont makes $4,900 per month. That is, they should only really be spending $1,470 a month on housing.

In other words, the average household cannot truly afford the average home. And this is likely consistent across other states, too.

But there’s a difference between affordable housing and Affordable housing.

The first is some nebulous term that’s seems to be tossed around casually. It has nothing to do with Area Median Incomes (AMIs) or quantified rents relative to what folks can actually afford.

Capital A Affordable housing, on the other hand, has to do with the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program and refers to projects that are heavily subsidized by federal, state, and local incentives in return for offering lower rents.

In fact, 70% of a typical Affordable housing project is paid for by LIHTCs with the remainder coming from debt, local subsidy, and deferred developer fees. In many scenarios, there is no private investor equity that would require a rate of return. That is, the developer can afford to offer the apartments at lower rents since they have very little skin in the game.

But the big misconception seems to be that Affordable housing projects are affordable to build. And they’re not.

Price per unit on a nearby 20-unit Affordable housing development came in around $250,000. That’s 2x higher than what we’re anticipating on our 9-unit project! Yet, they’re still able to offer rents at a 25% discount to our apartments.

Building Affordable housing is administratively intensive, though, and requires a back office function that most small-scale developers just don’t have.

Instead, us small guys are left to price apartments based on actual, unsubsidized costs with the aim at making them as affordable as possible. It’s not (usually) greed that drives rent prices up, it’s basic economics.

II.

I’ve started to notice more ~2 acre parcels cropping up as potential development sites in my area.

And nobody really knows what to do with them. Being in smaller towns, they’re outside the range of the larger regional apartment developers. But they’re also not best suited for single-family houses or duplexes given their central locations in town.

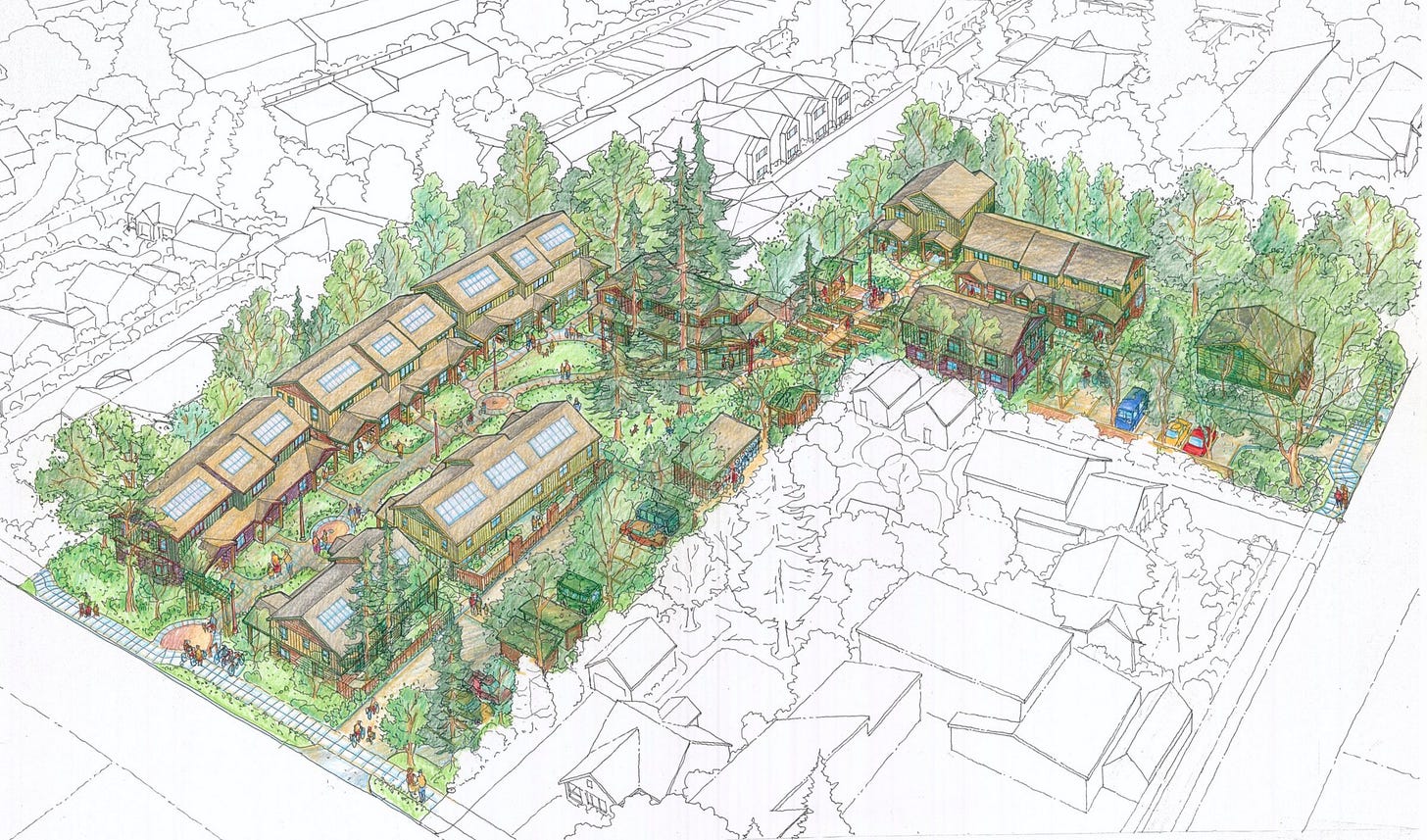

I’ve been doing a lot of research on Missing Middle housing types and recently came across one that I think has massive potential for these smaller parcels.

It’s called the cottage court. A few highlights:

1-1.5 story townhomes, clustered in groups of 2-3 townhomes

Units sizes between 600-900 sqf

Communal space, gardens, walkways, guest house, and other amenities at the center

Minimal parking (1 space per unit)

Emphasis on green space, community, walkability, and renewable energy

Take a look below. I’ve mentioned Cully Grove before but this is its newly proposed sister project, Cully Green—a 23-home new infill community on 1.5 acres.

Pretty nice, right?

So far, this Missing Middle model has been mostly used on the west coast. It’d be great if we were to see more of these communities in the Northeast. Perhaps a future project for Village Ventures.

1 PICTURE

I.

2013 vs 2020. Using local stone works to reintroduce original character and re-establish place.

📍 Poitiers, France

That’s it for today. Thanks for reading. If you haven’t yet, go ahead and subscribe here:

About me: I’m Jonah Richard, ex-Accenture Consulting and Columbia Engineering alum. I’m currently building Village Ventures LLC, a real estate development and investment company focused on creating great places.

Follow me on Twitter for more things related to real estate development and creating great places.