3-2-1: Repurposing A Vacant Gas Station, A Spat With VTrans, CA's Big Zoning News, & More

Week #8

Happy Sunday —

Here’s your weekly 3-2-1 from Brick + Mortar:

3 things from others

2 things from me

1 picture

Enjoy!

3 THINGS FROM OTHERS

I.

Not small-scale by any means, but worth sharing: Paris has set out to build its first ‘carbon-zero’ neighborhood.

This isn’t your traditional greenwashing eco-babble, either (looking at you here, Dezeen). Instead, there is a concerted focus to use materials that contribute fewer greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Whether as a result of transportation or manufacturing.

So, for example, 100% of the facade will be composed of natural materials including terracotta bricks, hemp and raw earth which come from the local region of Île-de-France.

Plus, 80% of the superstructures for all buildings are set to be built with cross-laminated timber (CLT) and stone of French origin rather than metal or concrete.

That’s cool and all. Until you remember embodied emissions (GHGs from material manufacturing) only make up 28% of emissions released from buildings. The big culprit is operational emissions (GHGs from heat loss and fossil fuel consumption), which account for the remaining 72%.

So give them a pat on the back and hope they’re following high performance building practices as well.

II.

LFG! A radical play by Gov. Newson out in California this week effectively ended the Golden State’s era of exclusionary single-family zoning. That is, zoning that only allows single-family houses to be constructed.

Form-based codes are in, boys and girls.

SB 9 and SB 10 advance the state’s policy to move towards objective, non-discretionary development standards.

In other words, gone are the days of the traditional zoning review meetings where committee members can make developers jump through hoops based on subjective and often arbitrary guidelines.

However, now, municipalities will be pushed towards developing graphically-rich form-based codes that clearly articulate design standards.

SB 9 also allows duplexes on single-family lots to be built by right (i.e. no discretionary design review process) and allows lots to be subdivided by two (potentially each with a duplex). Furthermore, it restricts off-street parking requirements—to zero if the lot is located near transit or served by car-share.

I tend to keep one eye open for progressive zoning policy changes (I’ve included them in my weekly updates here, here, and here). It’s funny how the majority of them seem to stem from California, Oregon, and Washington (although I threw in examples from NY and MI for good measure).

And out here in Vermont, we’re still debating whether to require 1 parking spot per bedroom or 2 parking spots per apartment (no joke, this is currently up for bylaw amendment).

III.

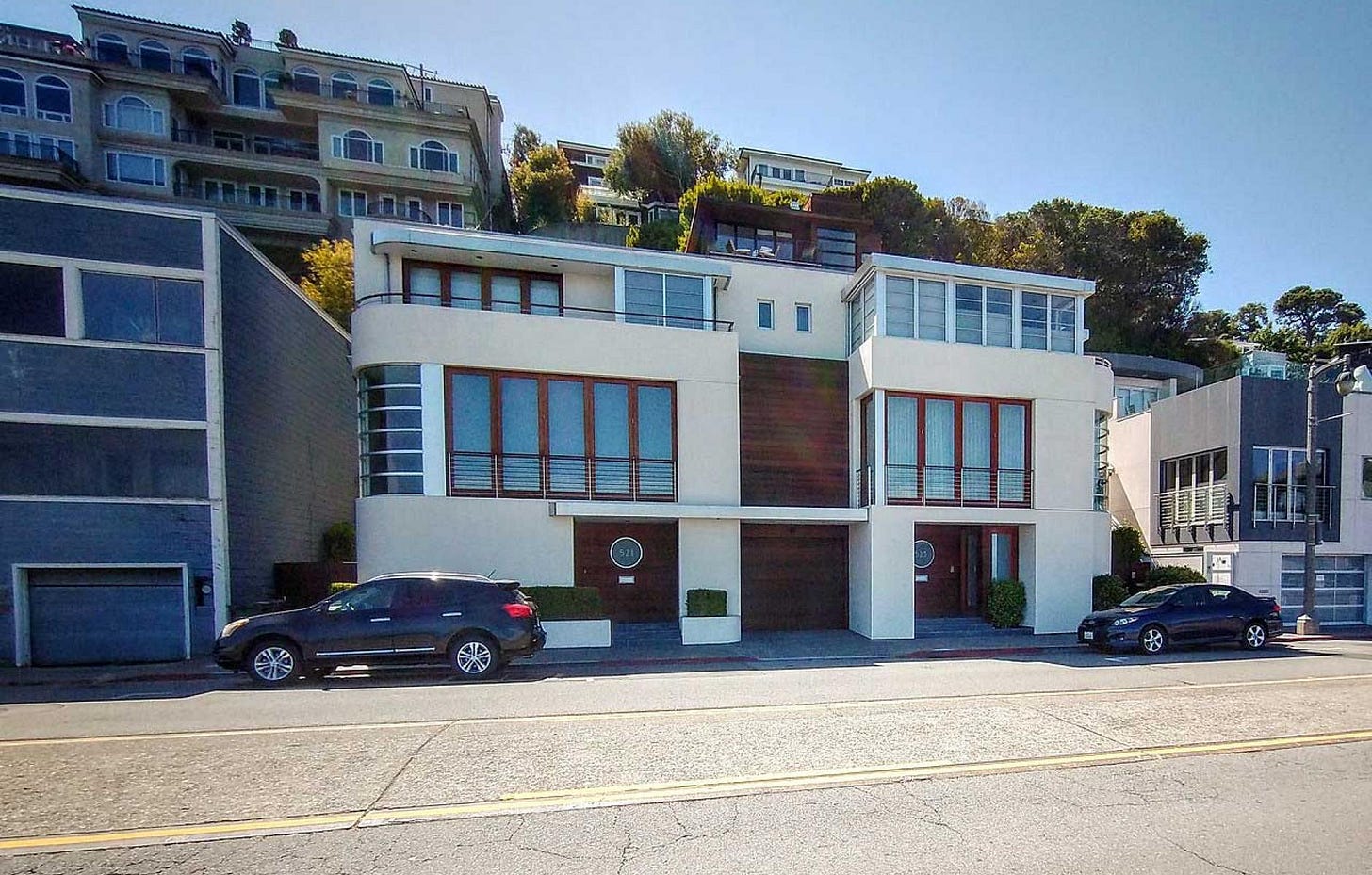

The right kind of infill townhome development. 🙌

2 THINGS FROM ME

I.

I did something Friday morning I never in a million years thought I would do. I woke up at 4:30 AM, did an hour of Excel work, then sent an email to a partner titled “Thoughts on accretionary effects of adding equity partners to <xxx> deal.”

I’m not surprised at the early wake-up call, my mind already racing about business problems that need to get solved or activities that need to get completed. I now write that off as coming with the territory of trying to start your own business.

I am surprised, though, that I would send an email with that string of words in the title. It just seems like the wrong mix of overeager private equity analyst and “look at me, I’m smart.”

But, hey—you can’t be too picky at 5:30 AM.

Anyhow, the reason for the email is actually worth sharing. If for nothing else than to showcase some of the dilemmas that small-scale developers face.

So here goes.

A few partners and I are under contract to purchase a vacant gas station (tanks removed in case you’re wondering). The plan is to do some sort of adaptive reuse project with the old building on site. Assuming our environmental due diligence proves out, that is.

We’re evaluating a few different strategies, including one where we whitebox the building and partner with a rockstar F&B operator to run a restaurant. Easier said than done, I know. But we have several good leads we’re working with. Plus, with $9M in annual restaurant sales leakage from the area, at some point you just have to give the people what they want.

Using rough numbers, we’re looking at a $650k project—$200k in acquisition costs, $200k to whitebox the station, and $250k to build out a restaurant concept.

Long story short, we’re trying to figure out the right ratio of debt to equity to get this funded and off the ground. Debt being from a lender (bank or private), equity being from a new investor or capital partner.

Generally speaking, more debt leads to higher returns (also higher risk). This is because debt tends to have a lower, fixed cost of capital than equity investment. Said differently—in exchange for a promissory note and mortgage, lenders will lend capital at lower interest rates than an investor taking a piece of the ownership would expect as a return on investment.

The more equity you involve in a deal, the more the proverbial profit pie is divvied up. Here’s an example. If Developer A buys and renovates a building for $500k with $30k in expected annual profits, he can either 1) purchase the building himself, say, with 25% down and 75% borrowed. Or 2) bring in Investor B at 25% so that now only 50% of the cost is borrowed. Making some assumptions on loan terms, Scenario 2 will have slightly higher profits of $37k per year (less debt service since only 50% of the cost is borrowed). If Developer A and Investor B are equal partners, then Developer A has a 24% cash-on-cash return in Scenario 1 [$30k / (25% * $500k)] versus 15% in Scenario 2 [($37k / 2) / (25% * $500k)].

Cash-on-cash return is just the amount of annual cash flow (after all operating expenses and debt service are paid) divided by the equity investment.

(By the way, these returns are only illustrative. Real estate is usually not that lucrative. If a developer or sponsor offers you cash-on-cash returns above 10% in Year 1… run.)

The addition of a new equity partner (Investor B) in Scenario 2 is considered dilutionary. As in, the developer receives a lower return on investment by bringing new equity into the deal instead of debt.

But, in the scenario we were running for the gas station, the opposite was true. Adding debt actually lowered the return on investment for equity partners.

As it turns out, this is because the cost of capital on equity was higher than that on debt. Because of the assumptions we made at the time (revenue, expenses, buildout costs, etc), our cash-on-cash return offered on equity was below our 6% cost of debt. In other words, the deal was actually sweeter the more equity we raised (i.e. raising more equity was accretionary).

The obvious conclusion on the surface is that this is just a bad investment. The average investor could expect to do better by simply storing their money in the S&P 500. Sure, different risk profiles but always worth a comparison.

To us, what that meant is we need to either 1) find a source of patient capital willing to compromise on cash-on-cash returns in exchange for establishing a legacy-building asset that contributes to the fabric of the community. Or 2) get creative with the deal structure and create more value for investors (e.g. a revenue share model with the restaurant instead of flat rent, or pass off some of the whitebox expenses to the restaurant).

Likely what we’re looking at is some combination of the two. There’s a deal to be made in most situations. And what I’m realizing is that it usually comes down to everyone’s ability and willingness to think a little outside the box.

II.

I started reading Chuck Marohn’s Confessions of a Recovering Engineer last week and I haven’t been able to put it down. It’s just so disturbingly relatable given my recent attempts to get a pedestrian crosswalk installed on Main Street this summer (which, ironically, is a state-owned road and therefore governed by state bureaucracy).

Marohn started his professional career as a transportation engineer, advising municipalities on industry best practices as it relates to shaping a city’s streets and roads. You know… the same best practices that make our Main Streets too wide and less pedestrian-friendly with more vehicles. Shoot—I mean safe.

In the book, Marohn recounts a somewhat fictionalized conversation between himself and a concerned homeowner on a new street-widening project. Essentially, he is tasked with convincing her of the merits of the project despite its obvious flaws.

What ensues is a blend of confusion, frustration, general tension, and perverse humor as they get deeper into the details. Marohn talks himself in a circle, ultimately exposing the hypocrisy of the project while exemplifying the insidious effects of poorly motivated and malinformed “growth.”

For some reason, they even made a strange movie with animated bears depicting the conversation. It’s goofy, but definitely worth a watch.

Anyhow, it got me all fired up about my summer-long saga with VTrans (Vermont Dept of Transportation) that I alluded to above.

Earlier this year, a few partners and I purchased a vacant lot along Main Street and proceeded to turn it into a quasi-park slash event space open to the public. You may remember the volunteer day we held in May. As a frame of reference, it just so happens to be adjacent to the gas station discussed earlier.

This summer, we opened up a coffee cart (Chapman’s Elixirs below), set up games, solicited a few art installations, and held a number of events that, given none of us are event planners, I would have called successful.

Pretty quickly, the site became a lot more active than it has been in the past 15 years. It’s also right on Main Street. Which, as you’ll notice below, is waaaayyy too wide in context. As a result, cars regularly travel 10+ MPH over the speed limit.

With multiple businesses, the town hall, and the town common on the other side of the street (that people on our side often walk to), we approached VTrans to install a crosswalk. Given that there had been one at the same proposed location 15 years ago, we didn’t expect any pushback.

Yet four months later, a site plan review, and the involvement of the town administrator, we have moved nowhere. Instead, the state has requested we conduct both a traffic and pedestrian-crossing study.

So much about this makes my blood boil. Just to name a few reasons:

It blows my mind how some people still think speed limits make cars travel slower. Cars drive at the speed they feel comfortable with. Period. Good street design makes safer streets and better neighborhoods, not arbitrarily imposed limits. Read this if you’re not convinced.

WTF is a pedestrian-crossing study? There is only one crosswalk on Main Street today and it is a mile south. I invited VTrans to come out and experience it for themselves. Crickets.

Main Street should not be a state-owned and maintained road. It should be the town’s. I understand and appreciate the financial implications of the town taking over responsibility but, like, Main Street is THE lifeblood of the Village Center. Without ownership over design, we’re never going to get to the walkable downtown we all want and crave.

And, then—get a load of this. A few weeks ago, VTrans sent their crew out to repaint one of the other crosswalks in town (not on Main Street). And, almost as if a big F*** you to us and the community for even contemplating a new crosswalk, they gave us one of the sloppiest paint jobs I’ve ever seen. I hope, at the very least, that the beers were cold.

1 PICTURE

I.

No parking requirements in King’s Landing, that’s for sure.

📍 Dubrovnik, Croatia

That’s it for today. Thanks for reading. If you haven’t yet, go ahead and subscribe here:

About me: I’m Jonah Richard, a small-scale real estate developer in Vermont. With my company, Village Ventures, I’m currently getting my hands dirty redeveloping mixed-use buildings along Main Street while trying to pick apart and replicate what makes other communities thrive.

Follow me on Twitter for more things related to real estate development and creating great places.