Dollar General At The Gates

The existential threat that Dollar General poses to small towns, a case study in Vermont, and what communities can do to avoid its death grip.

Welcome to issue #2 of Brick & Mortar.

Thank you to the 44 brave souls that entrusted me with their email addresses last week.

I’ll come right out and say it — I abhor Dollar General. Well, any discount or dollar store really, but I’m going to single out Dollar General here. Why? For one, they’re the largest of the national chains and pose the biggest threat to small towns. But, secondly, because they set up shop in the town I call home: Fairlee, VT. So, I guess it’s also personal.

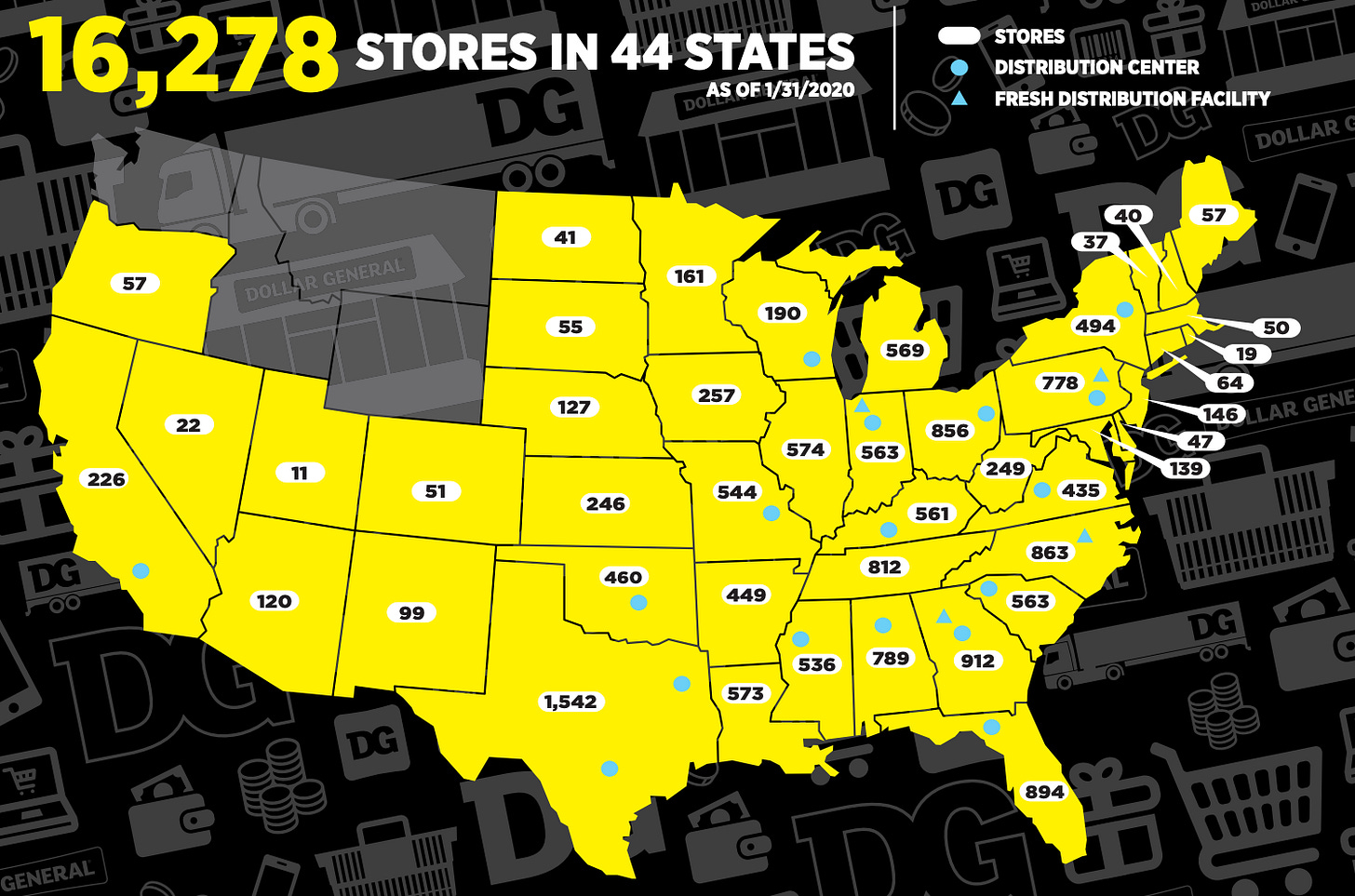

Granted, it’s next to impossible to rid towns of existing Dollar Generals. It’s much easier to prevent new ones from moving in. And, with nearly 1,000 new US locations opening every year, they pose an existential threat that should not be ignored. In this post, I dig into why that is (using a case study in Fairlee) and explore what others can do to prevent the same thing from happening in their communities.

If you like my writing and want to see more of it, just subscribe below (hint: it’s cheaper than Dollar General’s $1 Dollar Deals).

Enjoy.

A Few Ideas Worth Sharing

🎧 Listen: Upzone’s podcast on Gonzales, CA (pop. 9,000) charting its own course to energy resilience. As California’s largest multi-customer microgrid, 80% of electricity will come from renewable sources initially.

📺 Watch: Not Just Bikes’ latest video: The Houses That Can't be Built in America. A European’s take on our housing problem. As one commenter puts it, “No one does the dystopian aesthetic justice quite like Americans.”

📚 Read: Learning From Bryant Park — Andrew Manshel’s sage advice and tactics from his time turning Bryant Park in NYC around in the early 1990s. Packed with practical tips for placemaking in towns of all sizes.

The Big, Yellow Fox

Dollar General is like a fox in the henhouse.

Or rather, thousands of foxes in thousands of henhouse towns.

In fact, with 75% of its 16,000 stores located in towns with less than 20,000 residents, Dollar General may be one of the fattest foxes around. With record sales in 2019, they managed to extract $1.7B in profits from our communities.

But, just as foxes follow the rules of nature as they decimate their prey, Dollar General is simply playing the socially-acceptable game of capitalism. Survival of the fittest.

Yet, as much as the communities of these small towns like to denigrate Dollar General, it’s really no one’s fault but their own. And I do mean that in the sincerest way possible.

The fox has no morals, just instinct. In the same vein, Dollar General (or rather, its parent private equity company, KKR) only cares about its bottom line. Mom & Pop going out of business? Tough luck. I guess they weren’t competitive enough.

Dollar General is really only successful when two things happen:

The community lets them in

The community buys from their business

It’s easier to influence #1 than #2. Once the temptation is there, people will go. It’s a lot like junk food. I can resist the snack aisle in the grocery store all day, but once the Cape Cod chips are out of the bag and on the table, it’s game over. In the end, I would be much better off petitioning the grocer to ban the junk from the shelves and sever ties with his Fritos distributor. Effectively, cut the temptation off at the source.

In the same way, it’s important that communities (and planners, for that matter) understand the tools at their disposal to keep Dollar General out. For quite a few practical methods exist, as we’ll get into.

But, before we do, let’s take a look under the hood at the economic impact that these dollar stores have on local communities. Specifically, using an example close to home. Well, at least my home.

Case Study: Dollar General in Fairlee, Vermont

Fairlee is a Vermont town of 1,500 people with an average household income of around $50,000. Job opportunities in town are scarce and many residents either commute to an adjacent town for work or are retired (large, older population).

But Fairlee has a number of natural assets. The Connecticut River, two lakes, numerous hiking trails, and a golf course all provide a haven for outdoor enthusiasts. They also serve as seasonal economic drivers for local businesses.

However, economic development in the village center has been slow over the past decades, resulting in $23.9M in annual retail leakage. This is music to Dollar General’s ears.

To discount stores, retail leakage is the holy grail. In one number, it quantifies the level of consumer demand in an area by measuring how much local stores sell versus how much consumers buy. If consumption is greater than in-town purchases, that means residents are traveling to other towns to shop. A perfect opportunity to swoop in and provide a convenient alternative.

And that’s exactly what Dollar General did. In 2015, they cut the cheap, plastic ribbon on a shiny new 9,000 sq. ft. box on Main Street in Fairlee.

The decision to allow this to happen was short-sighted and erosive to the local economy. Here are three reasons why:

Job quality. Some folks like to argue that Dollar General brings jobs to the community. That’s like saying strawberry ice cream is healthy because it has fruit in it. Technically, yes — but there are a million better ways to get your nutrition.

Stolen sales and profits. Every dollar spent at Dollar General is one less dollar that could have supported local business. In addition, the profits generated are never recirculated in the community — rather, they get shipped down to corporate HQ in another state.

Low taxes per acre. Another argument in favor of these big retail stores (“big” here is relative to the standard 2,000 sq. ft. shop in town) is that they generate taxes. Again, that’s not wrong. Any structure generates property taxes. But, as we’ll see, it’s an extremely inefficient use of taxable land.

1 — (Under) Paid Labor

The average Dollar General store is 7,500 sq. ft. (roughly the same size as Fairlee’s) and employs a store manager, associate manager, and three sales associates. That’s it. All the other business functions (accounting, marketing, operations, etc.) are staffed out of corporate HQ.

Furthermore, unless you’re a Store Manager, the in-store jobs that are staffed locally are extremely low-paying. Not exactly what most town officials have in mind when they talk about bringing more jobs to town.

I want to be clear, though. Jobs such as Sales Associate are absolutely critical to have in any town or community. They can be solid opportunities that provide stability to local residents. There’s no debate there.

But at least pay them more! For a company raking in $1.7B in profit, would it really hurt to raise wages by $2.50 per hour (still not great, but better)? At least that would get them on par with average Sales Associate pay across the board. I’m no economist, but with 48,000 Sales Associates, this translates to an additional $240M in payroll per year. That might mean a 15% drop in profit, but c’mon guys.

When your average employee made $14,571 in 2019 but the CEO netted $12,008,059, you know you’re going to have an optics problem.

But what does the alternative look like? Would workers fare better in small businesses?

Public salary data for employees that work in small businesses is scarce. But, luckily, the US Census Bureau used to track and publish this level of detail (up until 2012).

In 2012, businesses with less than 20 employees in Orange County (where Fairlee is located) paid an average salary of $29,259. That’s roughly $14 per hour. And that was almost ten years ago.

Put another way, that’s 35% more than Dollar General pays its average Sales Associate today.

To me, that’s a good indicator that local job seekers would be better off financially if the Dollar General was replaced by a small business that actually cared about the success of its employees.

Of course, there are other factors to consider when job hunting. Things like work-life balance, healthcare, or retirement benefits are all important. But, consistent with their other compensation policies, Dollar General sets the bar pretty low here as well.

2 — Extracting $$$ From The Community

A good analogy for a local economy is that it’s like a bathtub with a bunch of holes in it.

Money (water) spent in town is added to the economy (tub) by the municipality (spigot) or consumer spending in town (buckets). At the same time, water is constantly leaking out from different holes (residents spending out of town; business owners sending profits elsewhere). Similar to the retail leakage concept above.

Ideally, a town is able to keep its tub full by balancing the inflow and outflow of capital. But what Dollar General does is drill a nice, big hole right in the bottom of the basin.

In 2019, the average Dollar General did $237 per sq. ft. in sales with a profit margin of 6.2%. Extrapolating that to Fairlee’s Dollar General, that roughly works out to $2.1M in revenue with $130k of profit after all expenses paid. That profit then gets packaged up and shipped straight to HQ in Tennessee, eventually landing in the pockets of the private equity investors that own the company.

While that might seem like a small drop in the bucket, keep in mind that there are only 150 registered, active businesses in Fairlee. Most of which are sole proprietorships and likely only do a fraction of the sales of Dollar General. Making some broad assumptions that the average business in town generates $250k in annual sales at similar profit margins, that would mean Dollar General is responsible for extracting 5% of all business profits made in Fairlee.

That’s a large share for a single business in any market. Especially when none of that money is being recirculated in the community.

Small businesses are the cornerstones of any community. They don’t just provide an outlet for entrepreneurs — they form the fabric of downtown vitality. Without them, we lose some of the connectedness we feel to our towns and to each other.

Imagine the impact if that $2.1M was spent across local businesses instead. We’d get more local wealth creation; better jobs with locally-sourced accounting, marketing, and operations talent; and improved quality of life for residents with a more vibrant village center.

3 — “Buy Land, They’re Not Making It Anymore”

Taking Mark Twain’s investment trope one step further, Strong Towns advocates that land is the base resource from which community prosperity is built and sustained. It must not be squandered.

In 2020, the Dollar General in Fairlee paid $24,081 in property taxes.

Great. Some people think. That’s $20,000 more than that vacant lot was generating before.

Factually, that may be correct. But, there’s a little more to it than that.

The Fairlee Dollar General sits on 1.72 acres of prime Main Street real estate. That translates to about $14,000 per acre in property taxes.

What would happen if that lot had been subdivided and developed into smaller commercial or mixed-use buildings? How would that impact the town coffers? Fortunately, we have some actual data to play with.

Specifically, let’s compare Fairlee’s 2020 tax revenue from a few different commercially-zoned properties on Main Street.

All of a sudden, the big retail store isn’t so attractive from a town revenue-generation standpoint. It’s just not an efficient use of taxable land. Sure, it’s better than nothing. But is that really the bar we want to set?

Instead, it seems it would actually be within a town’s best interests to promote small-scale mixed-use development. Not only would that improve downtown walkability and vibrancy — the town could actually generate 1.5-2x more taxes from the limited land available.

Certainly, there are instances where larger retail developments are beneficial. Foggs Hardware in Fairlee is a great example. At 15,000 sq. ft., Foggs generates only around $3,400 per acre in property taxes. Granted, it likely does not need the full 5.3 acre site, but it does provide an important service to the town: building supplies. Plus, it is a small business with only a handful of locations.

Want to do a similar analysis for your town? Check out Strong Town’s Value Per Acre Analysis: A How-To For Beginners.

Not All Big Chains Are Bad

Most are, but not all.

For example, take Hannaford Supermarket — a 45,000 sq. ft. grocery store just one town north of Fairlee in Bradford (population 3,000). Not only does the store have roughly 200 locations, but it is also owned by an international corporation based in the Netherlands called Ahold Delhaize.

The difference is that Hannaford provides real value to both the immediate and surrounding communities. In the form of fresh produce and healthy foods at affordable prices. They also make an active effort to establish partnerships with local food vendors.

Furthermore, the broader community was lacking a good grocer prior to Hannaford moving in — it’s not like the company came in and undercut the local competition.

Dollar General, on the other hand, built and opened a new store literally 500 feet from the local alternative in Fairlee. And they didn’t even offer a new service, like the pharmacy in a CVS or Kinney Drugs. Instead, they just sell more prepackaged and plastic shit at a discount.

Where Do You Draw The Line?

This argument then begs the question — so what types of businesses are acceptable?

In some part, what I’ve suggested does run counter to traditional American free-market ideology. But unfettered capitalism has consequences. I’m not anti-capitalist — I’m just pro small town.

Our federal government puts tariffs on foreign goods to prop up domestic manufacturing. And, in the same manner, there must be some level of acceptable intervention for small towns to preserve and foster their local economies.

That said, where we draw the line is not black and white. It’s not as simple as setting a restriction on square footage, employee size or number of locations. It’s more subjective than that.

Instead, each town will have its own guidelines, tailored to the individual needs of the community. The important part is that it is a collective decision, not one administered from the top down.

Cigarettes are legal. But there’s a reason why no doctor would prescribe or recommend them to a patient. They’re just not conducive to maintaining a healthy body.

In the same way, we need to be more cautious and prescriptive in what we feed to our small towns.

There’s Still Hope Yet

For those of us in towns already occupied by the dollar stores, there’s little hope. It’s a done deal once the town approvals are in hand and the business is fully established.

But, for those of you with dollar stores at the gates (or fear one coming soon), there are a few preventative measures the community and town can take. In doing so, hopefully, you’ll be able to avoid the situation I described above with Fairlee.

The Institute for Local Self-Reliance is a great resource for this. Their motto is: Building local power to fight corporate control — just what the doctor ordered.

Here are a couple ways to stop a big box store:

Button up your town’s comprehensive plan. The comprehensive plan lays out the community’s vision for their town and provides a guide for local regulations, community investment, and economic development. For example, it may designate the village as the commercial center or specify facade design constraints for new development. In most states, failure for a new project to comply provides the town with legal recourse to reject it.

Require a variance for retail stores above a certain size. This is done using zoning bylaws, which effectively regulate the implementation of the comprehensive plan. Lot sizes, parking restrictions, height and size of structures — all can be controlled through zoning. If the discount store exceeds those thresholds, they can be denied approval.

Impose an economic impact study. Some towns are implementing policies that require big retailers to address the effect their business will have on the local economy. This includes the impact on existing businesses, the vitality of the downtown, employment (jobs gained versus jobs lost), wages, tax revenue, and municipal costs. And, if the findings are negative, the town can reject the project.

Get the community involved. Many of these projects require a public hearing. Get out there and voice your opinion. Rally your friends and neighbors. Make as much noise as you can so that local decision makers understand the negative impact this will have on the community. Most town officials are well-intentioned, they just may be uninformed.

At the end of the day, it’s up to us — members of our communities — to fight this off. There is too much at risk if we don’t.

Thanks for reading.

Until next time,

Jonah (@jonahhrichard)

Interesting analysis. However, I would like to know whether retail leakage in Fairlee, omitting Dollar Store sales, has risen or fallen since the store arrived. An additional shopping destination might bring extra visits to Fogg's, Chapman's, the hairdresser, etc. For the record, I shop at Dollar General only in moments of desperation, e.g., Chapman's closed and Christmas present must be wrapped and mailed, no paper left.... or when they have something no one else in town has.

A little background. When the Dollar General came to town Fairlee had absolutely no regulatory means to stop the development. The bylaw was woefully outdated, the electorate divided on whether there should be zoning in the first place, and there was a basic malsie in what was seen as a dying village.

At least DG coming to town focused the mind and began a dialog. We are now ten years out. We have a robust Town Plan, Unified Development Bylaw, an activated and educated Selectboard, local citizen groups which spouted eight years ago have matured into a force for community life. The Town now takes its future seriously and a real consensus supporting housing and scaled economic development.

As the planning professional in town a DG would not have been my druther to inspire this village renaissance but you use what you have at hand, this would not be the first town whose revitalization was trigged this way. The best is yet to come, we are beginning to see the fruits of a decade worth of study, planning and hard work.