A Bite Of The Big Apple

Comparing development economics of a 51-unit project in Brooklyn to a 9-unit in Fairlee, VT.

Hey — Jonah here. This is Brick + Mortar where you get insight into the acquisition, financing, design, construction, and operations of small-scale real estate development projects.

First, an update on 501 Main. Then, a look at NYC development economics vs what I’m seeing in Vermont.

501 Main update

Real estate development in NYC vs Vermont

I saw this on Twitter the other day.

I lived in NYC for awhile and was always curious how deal economics worked there. Especially now that I’m working on projects of my own in Vermont.

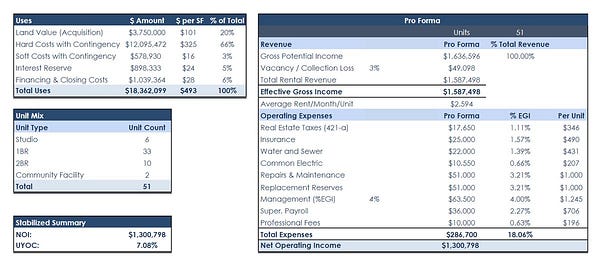

Here’s what a 51-unit new construction project in Brooklyn looks like under the hood:

Curiosity be damned!

I should be developing in NYC.

There are some glaring differences between the small-scale projects I’m working on Vermont.

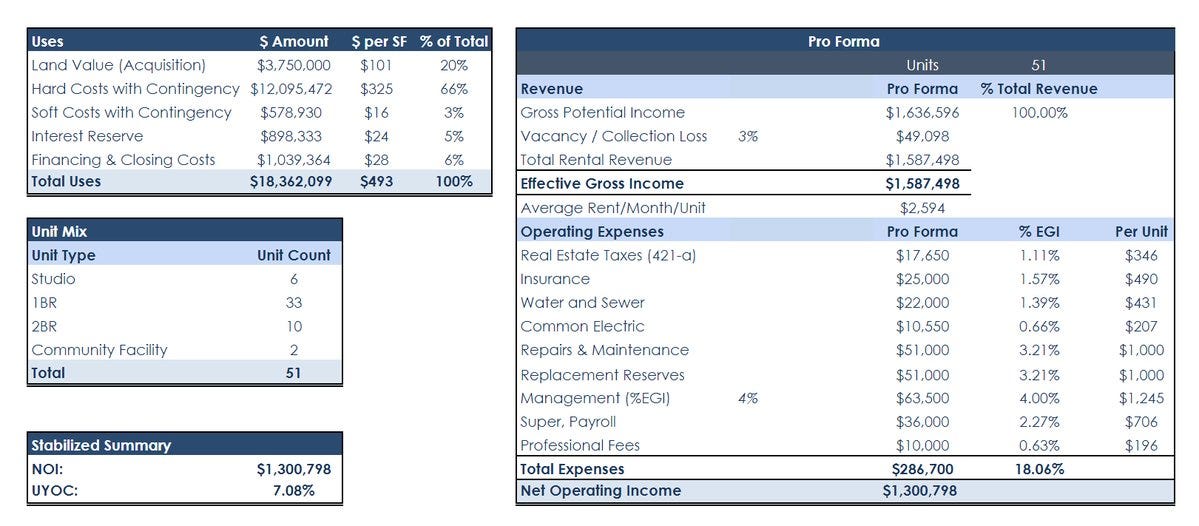

So I decided to create a similar template for 501 Main to compare against Eli’s:

A few definitions:

NOI = Net Operating Income, or income after expenses are paid but before debt costs. Like EBITDA in the business world

UYOC = Unlevered Yield On Cost, calculated by dividing NOI by the total uses (project costs). Useful for comparing investment potential across real estate development projects because it doesn’t account for debt structure

Let’s compare the two projects.

Three observations stand out to me:

#1: Property taxes

Eli’s project gets a 421-a tax abatement.

In exchange for keeping 30% of the units affordable, the project temporarily receives a ~90% reduction in taxes. It’s not clear for how many years (5, 10, 15?), but still. That’s a massive incentive.

From what I gather talking to local government in Vermont, tax abatement is extremely rare here and requires a public vote for each property. The majority of towns do not have a defined program for developers to take advantage of.

Vermont towns need a better mechanism to grant tax abatements. It requires long-term vision from the town—sacrificing short-term revenue in exchange for economic growth, revitalization, and increased revenue indefinitely once the abatement expires.

But what a powerful way to spur new projects, many of which won’t pencil today without abatement.

Until then, I’ll continue to pay 4x the property taxes on a per unit basis at my rural projects in Vermont when compared to NYC.

#2: Operating expenses

Eli pays 18% of gross income towards operating the building.

I pay 40%.

More than double.

This impacts profitability, raising equity, and supporting debt. That is, the higher that expense ratio, the less income is available to make mortgage payments and pay investor returns.

A lot of this has to do with economies of scale—if I built a 51-unit project in Fairlee, I imagine the project would see some relative savings.

But I didn’t. And so we’ll just add this to the list of disadvantages to building small-scale.

#3: Build costs

Construction costs more in cities. I think we all know that.

$493/SF vs $314/SF fully delivered.

All I’ll say is that we’d be belly up right now if we were building for $325/SF in hard costs.

Another way to look at it is in terms of cost per unit:

Eli: $359,000/unit

Jonah: $147,000/unit

A bit apples-to-oranges since different markets, construction types, unit sizes, etc.

But fun to quantify that difference. Especially when I’m on the lower side.

A parting reminder: NOI is not the same as developer profits.

I am not making $76,000 each year on this deal.

Almost 100% of that will go towards paying off debt and investors.

It’s important to recognize that investors take huge risks putting their capital in development projects. And the only way to incentivize investment is by offering a return on capital.

Without it, our built environment would look a lot less… eh… built.

Until next time.

— Jonah 🧱